Overview

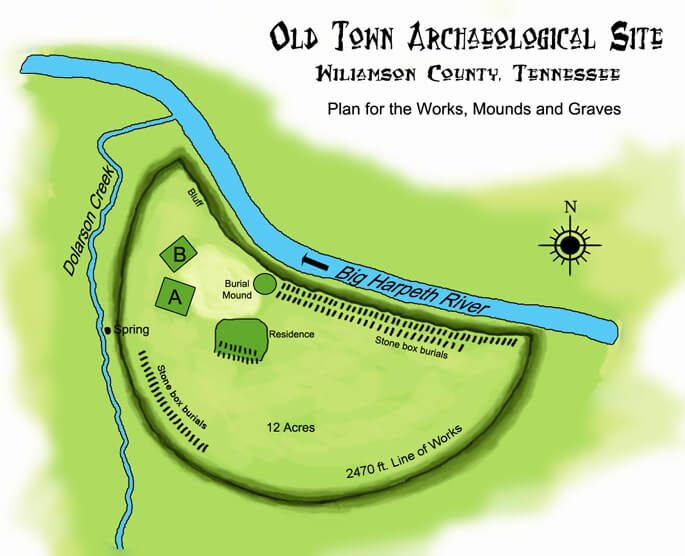

Places on the landscape are imbued with meaning by those who experience and interact with them – and by those who remember and pass on their past stories. The Old Town Heritage Project is about remembering, celebrating, and preserving one very special place on the landscape that has served as a point of contemplation for many dozens of generations – from the earliest Native American settlers of Middle Tennessee over 12,000 years ago to the more recent peoples of the American historic era.

Launched shortly after Bill and Tracy Frist purchased the 41-acre property in 2015, the Old Town Heritage Project is a collaboration with Middle Tennessee State University designed to add to the limited body of knowledge of what is today known about ancient civilizations in Middle Tennessee. The Project supports academic-led discovery of the ancient history of Middle Tennessee and the broad distribution and sharing of that new knowledge with the public and future generations.

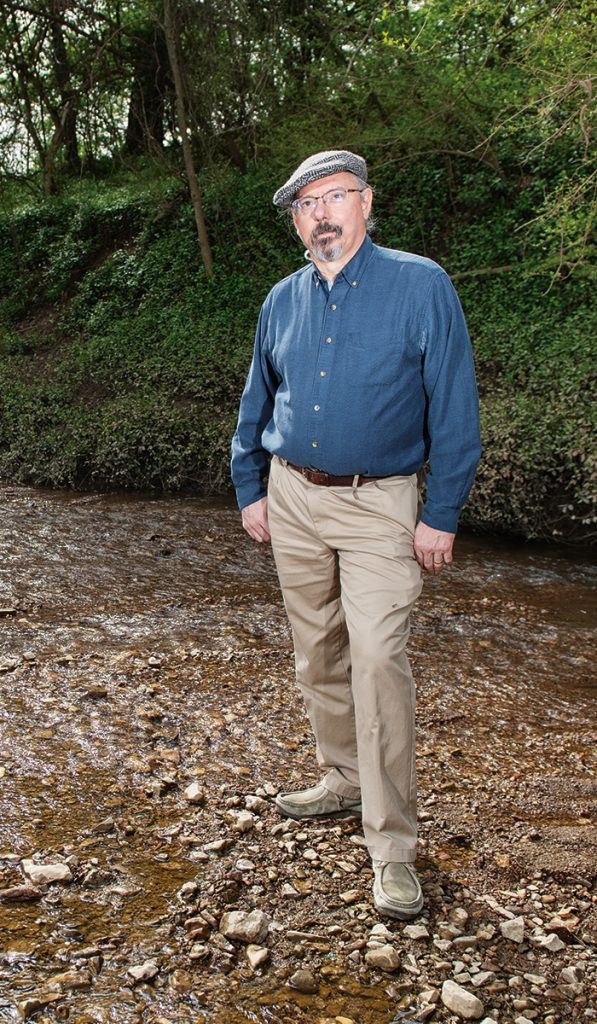

The scientific research component of the preservation effort is led by MTSU Anthropology Professor Kevin E. Smith, PhD. Smith had long been familiar with the site, having first explored the property superficially some 25 years ago at the request of previous owners. He has published extensively on the archaeology of the southeastern United States, and hopes through this project to garner a much richer and more complete understanding of the untold prehistoric history of Middle Tennessee.

Professor Smith explains:

“This is a town, not just an archeological site. People lived here and had great leaders. We only have about three such sites in state ownership and two in private, so this is a new addition. This is the first concerted effort by a private landowner in middle Tennessee to take it upon themselves to preserve it as the state would if they owned it. … There used to be about 40 towns like Old Town all along the Cumberland River and its tributaries. There’s also great farmland here, which supported their economy. It was one of the most densely populated areas east of the Mississippi in the prehistoric era. Geographically, it was the center of the trade routes in all directions.”

The multiple earthen mounds that mark the Old Town site as an ancient civilization range from 4 to 12 feet in height and, according to Smith, “were some of the largest earthen constructions built in middle Tennessee until the 1950s. We didn’t have the ability to build these types of structures until we got bulldozers, and they did it with baskets.”

Smith, who has studied six other mounds in the region since the 1980s, said they played important, multifaceted roles in the lives of those who lived in the community. “Mounds like this are platforms that elevate; they are the same as Maya temples [in Guatemala] atop a pyramid. These in middle Tennessee were built with earth and on top were houses for the kings of these towns and their families and temples.”

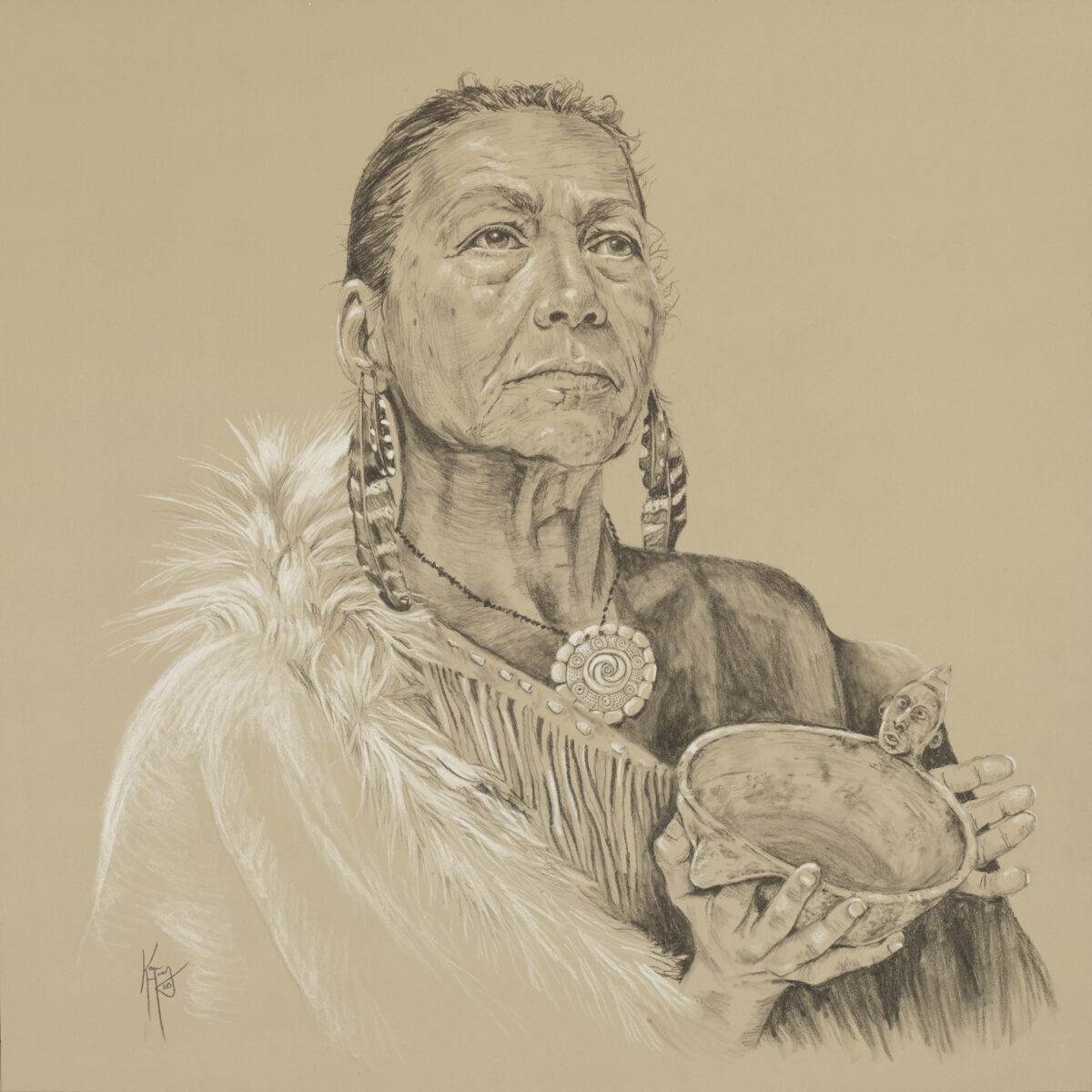

In addition to being known as the “Mound Builders,” the Mississippian people cultivated a rich, highly developed artistic tradition. “In many ways, it was the most fabulous art tradition that ever existed in North America,” Smith said. “Much of Mississippian art centers on things that took place at the time of what they viewed as creation, with depictions of supernatural heroes who cleared the earth of monsters so humans could live here—much like the hero twins associated with the Maya civilization. The other part of the Mississippian peoples’ art dealt with what happens to the soul after the body dies. Their art explored the possibility of reincarnation.”

To respectfully investigate this rich history, Smith is overseeing exploration with non-intrusive, high-tech archeology using magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar to map the Old Town site out without disturbing it. Employing the services of New South Associates, Inc., the Old Town Heritage Project commissioned completion of a large-scale “archaeological geophysics” survey of the majority of the Old Town farm. Smith shared that, “If the soil chemistry cooperates, we’ll have a picture of where the houses were located, as well as where the cemetery and graves were located, and a more precise idea of where the original town wall was located. And all of that can be done without turning over a spade of soil. Then, with the input of all the stakeholders, we can decide whether we’ll do some limited archeological work to answer specific questions without disturbing any graves or destroying anything.”

The survey involved two very different survey instruments and techniques – gradiometer and ground-penetrating radar. The gradiometer measures local variations in the earth’s magnetic field – an instrument that can detect buried features such as burned posts, concentrations of bricks, burned buildings, and hearths. Since much modern metal debris is highly magnetic, even items as small as nails can obscure large areas. As a result, this instrument was only employed on 3.14 acres in the north pasture – away from modern fencelines, utility lines, and buildings where metal debris is less likely.

In contrast, ground-penetrating radar sends a pulse of radar energy into the ground – when it reflects off buried objects, features, or contacts zones between different density bedding contacts, a receiving antenna on the instrument detects and records these. The ground-penetrating radar survey covered 7.3 acres of the current Old Town farm property.

This modern high-tech approach to archaeology permits a detailed glimpse of what lies beneath the ground with two major advantages: 1) no ground disturbance that might affect surviving site features (e.g. pits, structures, graves, roads, pathways) is required; and 2) large areas can be examined much quickly and efficiently than “digging.”

The final report on these surveys is under review. As a teaser, we can already state that these surveys revealed a number of amazing historic features (portions of the early 1800s Natchez Trace, buried sidewalks and gardens relating to the Brown house) and many prehistoric houses, temples, and public buildings.

As part of the Old Town Heritage Project, Bill and Tracy Frist have engaged a diverse set of stakeholders to provide valued input on how to best preserve the many layers of Old Town’s history. This includes, but is not limited to, the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County, The Harpeth Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy, and the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

To this day, Old Town offers what it has for many generations – a place to find peace and serenity while contemplating the past, present, and future. The preservation and conservation of the land and legacy for generations to come is Bill and Tracy Frist’s passion and mission in establishing the Old Town Heritage Project. Please check back here for the latest updates on the discoveries, newly uncovered history, and progress made in documenting and protecting the many lives lived on these storied and well-loved grounds.

Lady of the harpeth

Project Update

Sources:

Campbell, Darby D. “Saving Old Town.” MTSU Magazine. 1/25/19.