Archaeological research at Old Town has been limited in scope and primarily restricted to salvage excavations. Most archaeological records concerning Old Town are based on antiquarian excavations. Their early archaeological reports do not meet present-day documentary and curatorial standards; however, they provide some of our only insights into the archaeological site.

JOSEPH JONES

Joseph Jones was the health officer for the City of Nashville between 1868 to 1869. During this time, he excavated many archaeological sites nearthe city, including Old Town, which he described in detail (Jones 1876; Moore and Smith 2009). Old Town was recorded as 12 acres enclosed by an earthwork or palisade (Figure 3). The site consisted of two “pyramidal” mounds measuring 9 and 11 feet high, a circular “burial” mound, and an additional mound on which the mansion was constructed. In the course of his excavations, Jones identified and trenched through the two large mounds (known as mounds A and B). Jones indicated that the mounds were built in several building episodes and that the mound tops from each building episode were baked, “the heat of which was sufficient to bake and redden the earth for some inches below” (Jones 1876:86). He also mentioned an 1852 schoolhouse building on the larger of the two mounds, where several burials were identified during its construction.

The palisade around the site was still visible at this time, although Jones indicated it had eroded and that local residents told him that previously, it was much taller. He also noted that the Brown mansion appeared to be atop a mound and excavated around yet another burial mound (“burial mound” on the historic map). Jones excavated somewhere between 60 and 75 graves (Smith 1993:29). In his text, he describes a number of grave offerings and skeletal remains.

WILLIAM M. CLARK

In 1875, William M. Clark, a local doctor, explored several mound sites within Williamson County, including Old Town (Moore and Smith 2009:101; Clark 1878). Clark (1878:274) excavated an unknown number of burials and noted that many had been dug before he visited. According to Clark, the palisade had been removed or eroded at that point, the mounds had been “dug into,” and “most of these graves have long since been emptied of their contents.”

PEABODY MUSEUM EXCAVATIONS

Fredric Ward Putnam of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum conducted and supervised numerous excavations in Middle Tennessee and throughout the Southeast (Moore and Smith 2009). These excavations were undertaken with the explicit goal of increasing the museum’s collections. Specimens from the precontact sites along the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers make up one of the museum’s largest collections and together form one of the largest single collections of Middle Tennessee diagnostic artifacts held by any institution (Moore and Smith 2009:1). Putnam’s chief assistant in the area, Edwin Curtiss, spent a brief period exploring Old Town in October 1878. He dug six stone-box graves along the side of the road, but stopped after a day, noting the graves had been damaged by wagon traffic (Moore and Smith 2009:99). The only artifact recovered was a ceramic earspool.

W.G. POLK

In 1928, W.G. Polk investigated approximately 80 stone-box graves at the junction of the Harpeth River and Dolarsen Creek, prior to their destruction by machinery during construction of a bridge (Polk 1948; Moore and Smith 2009:101). His observations were limited, but Polk describes several funerary offerings and a variety of burials (Smith 1993:33), including one particularly large stonebox burial measuring 7×2.5 feet (2.1×0.8 m) containing two bodies, one male and one female.

TENNESSEE DIVISION OF ARCHAEOLOGY

The Tennessee Division of Archaeology (TDOA) excavations at Old Town were conducted as a result of salvage operations at the property owner’s invitation in 1984 and 1991. No controlled excavations have been done by the agency on site (Smith 1993:33). In 1984, a privately funded waterline was constructed on the property, and TDOA archaeologists were allowed to make some observations during construction. The trench for the water line was approximately 3 feet wide (0.91 m) and within the right-of-way of Old Natchez Trace, both underneath and adjacent to the road (Fielder et al. 1988). Archaeologists observed a number of stone-box graves and a burned structure, as well as a number of ceramic, lithic, and faunal artifacts.

In 1991, a renovation to the Brown House required the excavation of footings behind the house. TDOA archaeologists analyzed artifacts recovered during construction. They also drew profiles of the footings holes, excavated a partially destroyed pit, and recorded a single stone-box grave. The burial was not excavated (as dictated by Tennessee Cemetery Statutes), but the decedent was noted to be a juvenile male. The pit feature appeared to be used for the disposal of trash and dates to the precontact period. The corrected radiocarbon date from a piece of charcoal in this feature dates to 1215. This date, along with other diagnostic artifacts from the 1991 and 1984 excavations, suggests that the site’s major occupation was likely between 1250 and 1450, or during the Thruston Phase (Smith 1993:35). The porch observations and excavations could not conclusively confirm or deny Jones’s hypothesis that the Brown House was placed on a burial mound.

By Nick Fielder

Drawn at Old Town temple mounds

NEW SOUTH ASSOCIATES GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY

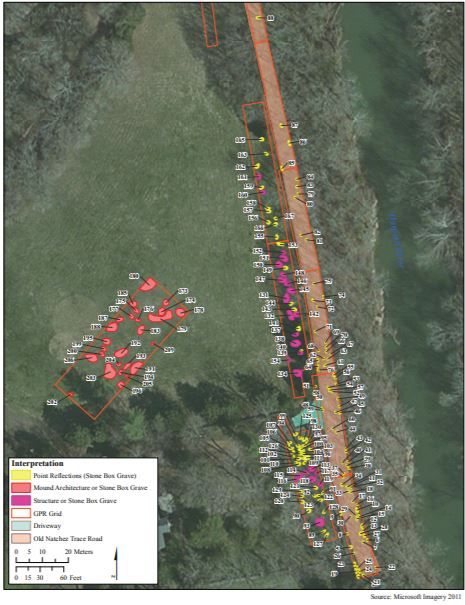

In 2014, at the request of the landowner and in advance of planned work on Old Natchez Trace, New South Archaeologists conducted a GPR survey of Old Natchez Trace and the land adjacent to the road, totaling approximately 1.15 acres (Figure 4)(Lowry and Patch 2014). GPR results detected 211 total anomalies and 182 anomalies with characteristics suggestive of graves. The results indicated a number of precontact features and that the site continues underneath the present-day road.

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

The Thomas Brown House, the Old Town archaeological site, and the adjacent bridge are all listed on the NRHP. The Thomas Brown House (WM-347, also known as simply Old Town) was listed in 1988 under Criterion C for architectural significance (National Register Keeper 1988a). The circa 1846 two-story antebellum mansion and smokehouse both contribute to the listing. The Old Town archaeological site (40WM2) was determined eligible under Criterion D, with potential to provide information about the Mississippian period in the Central Basin, and was listed on the NRHP in 1989 (Fielder et al. 1988). Finally, the Old Town Bridge (WM-47)is listed under Criterion A as the only remaining bridge site on Old Natchez Trace (National Register Keeper 1988b). The limestone block bridge was built in 1801 spanning Brown’s Creek and was an important part of the historic road system. The bridge was replaced around 1913, but the original limestone block abutments remain in place.