Kevin E. Smith (Middle Tennessee State University), William H. and Tracy Roberts Frist (Old Town), and Sarah Lowry (New South Associates)

When you purchase a house and farm sitting atop of a major Middle Cumberland Mississippian mound center like Old Town in Williamson County (ca. AD 1100-1450), you can opt to ignore it in the name of progress – or you can accept the responsibility as stewards to actively preserve this part of Nashville’s prehistory while still maintaining a working farm and residence. In this case, we chose to establish to partnership between the private owners and scholars at Middle Tennessee State University to create the Old Town Heritage Project (OTHP). The primary goals of the OTHP are to expand our archaeological understanding of the site through scholarly research, to provide information that will enhance the ability to preserve sensitive and key parts of the site, and more broadly, to sponsor products that will enhance both regional and national understanding of the Mississippian culture that occupied the Nashville area from about A.D. 1100 until 1475. The current Old Town farm contains three major components (each listed separately in the National Register of Historic Places): a) the Thomas Brown House, built ca. 1846; b) the Old Town Bridge, built in 1801 by federal troops as part of the Natchez Trace; and c) an estimated one half of the Mississippian town (Figure 1).

Over the past three years, the OTHP initiated several projects designed to further those goals, including documentation, analysis (and re-analysis) of all known artifacts from Old Town held privately and at museums throughout the eastern U.S. (Figure 2), and a workshop series bringing together the private and public land managers of Middle Cumberland Mississippian sites and collections (Figure 3) to engage in developing a proposed “Middle Cumberland Mississippian Sites Trail” that links together and coordinates interpretation at these sites in a broader and more comprehensive fashion.

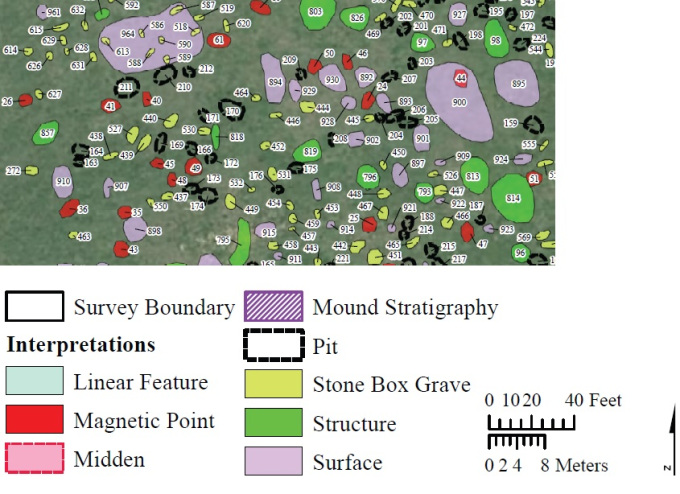

Most recently, the OTHP secured the services of New South Associates, Inc. to complete a very large-scale archaeological geophysics survey, including 3.14 acres of magnetic gradiometry and 7.3 acres of ground-penetrating radar (Figure 4). While the final report is still being reviewed and finalized, we can already note that it was a stunning success – creating new insights, new research questions, and new management plans to protect both the prehistory and history of the property.

Just for a few teasers at this point, in the front yard of the Thomas Brown House, a currently otherwise invisible and previously unknown circular sidewalk around the front yard was suggested by the GPR – bisected east-west by a sidewalk running from the front of the house to a (previously) mysterious gate in the stone wall (Figure 5). At this point, we are still re-visiting documents and photographs – but it seems very likely this is a mid-late 1800s yard feature associated with the Brown family, whose flower bed encompassed much of the front yard in the 1860s. Based on contemporary front yard and garden paths in Middle Tennessee, it is likely a gravel path edged with brick or limestone – some controlled testing of segments will be in the works for the future.

For the prehistoric components, the survey reveals that there are hundreds of probable pits, graves, residential structures, special purpose structures (temples), and others still preserved in parts of the site – despite more than a century of agriculture, utility lines, and other disturbances (Figure 6). Some of the anomalies interpreted as ancient structures (e.g. 793, 796, 857) are consistent with the size of Mississippian houses (about 15 feet square and about the same size as early historic log cabins). Others (814), however, are clearly much larger and are most likely special-purpose buildings – workshops, temples, and elite residences.

While we all understand that these geophysical glimpses are only guides to and interpretations of what might or might not be beneath the surface – let us say these are the most scientifically informed guides available to us on the large scale. We have already used the preliminary results earlier this summer to select an area for a necessary major ground-disturbing activity. We avoided areas with high potential for important features and picked an area that seemed to have little geophysical potential. The selected area, monitored during excavation by the senior author with accompaniment by the Frists, indeed proved to have nothing of significance – no midden, no features, and no artifacts. So much so that we now suspect that this part of the site was used as a borrow area in the 1940s or 1950s to gather dirt for the current Old Natchez Trace levee.

Obviously, there will be many more things to come from the OTHP. As time passes, however, we intend for this to stand as a model for partnerships among private landowners and scholars to protect, preserve, and learn about the few remaining Middle Cumberland Mississippian sites out there.