While the historic bridge, home, and stone walls are visible reminders of the past two centuries of people who traveled and lived at Old Town, the most ancient architecture preserved here are the earthen monuments constructed by the ancestors of modern Native Americans who settled here almost a thousand years ago.

Sometime between about 1050 and 1350 AD, ancient Native Peoples gathered here to construct a 12-acre town — replete with dozens of houses, places of worship, and other community buildings. While the centuries have left few remnants visible on the surface, the three most monumental of the things built during those times remind us of their presence – the two large earthen mounds to the north of the historic residence and portions of the fortified wall that surrounded and protected the town.

The mounds directly in front of the home include the burial sites of tribal kings and queens, according to archaeological historians. The Mississippians were a highly developed people with highly organized class structure; they were known as the “mound builders.”

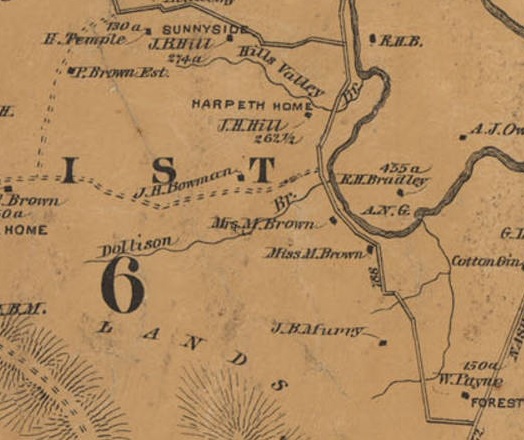

The earliest historic explorers of the region — visiting almost three centuries after the town’s native inhabitants moved elsewhere — immediately recognized that this had been an occupied place long ago. A mystery to them, they referred to it as “the old town” — a name that later also became attached to the Brown home and the farm itself.

The mysterious mounds and earthworks attracted much attention from locals and antiquarians alike — probing often indiscriminately in the mounds and graves of the ancient residents in search of both clues and “treasures.” Lacking the skills and tools of modern researchers, their explorations are important today largely only as historical records of the long-held interest in the Mystery of The Old Town.

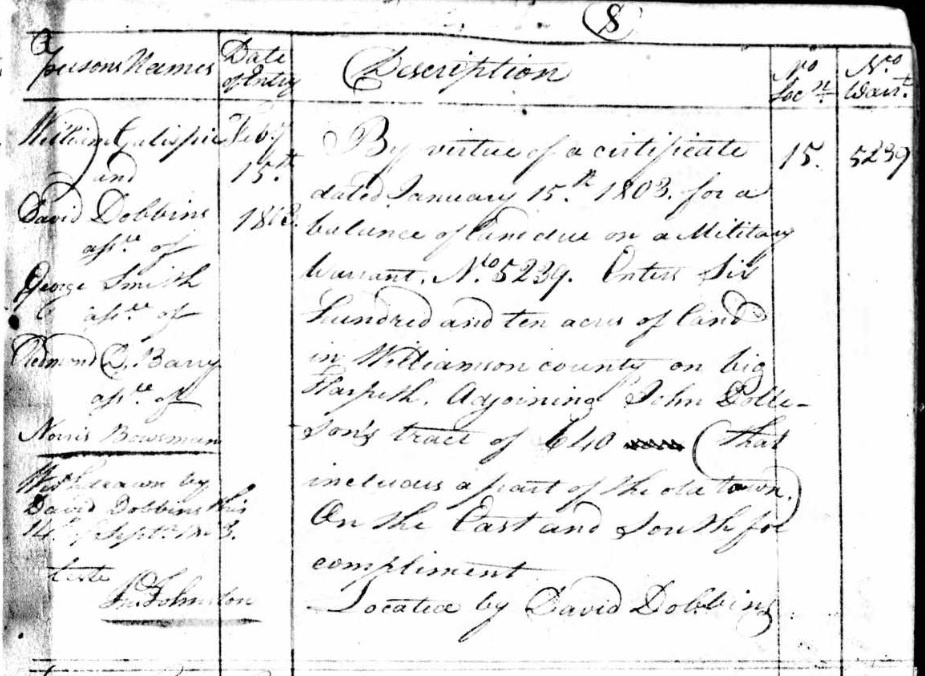

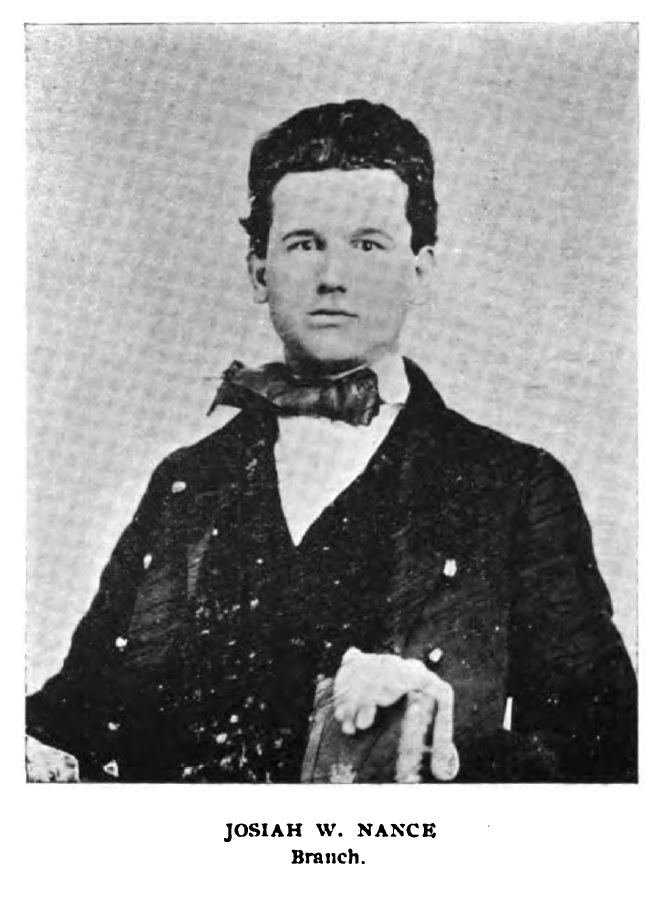

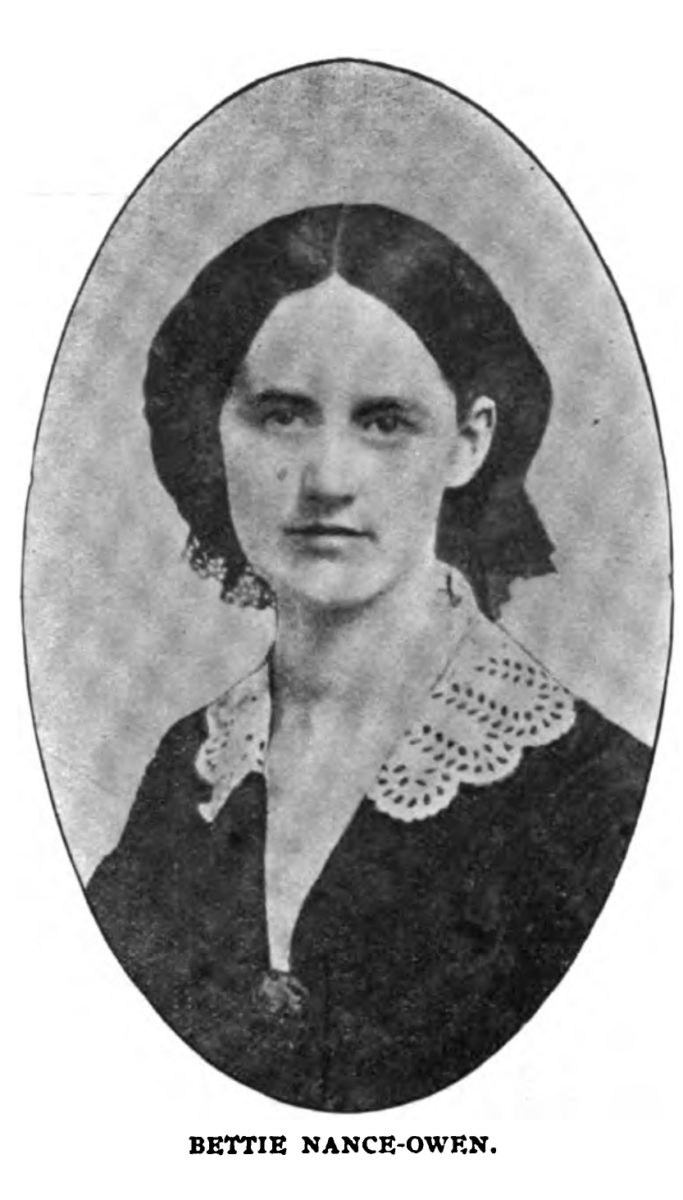

On 1 Oct 1856, J. Nance wrote to his sister Elizabeth Morton Nance from Hill’s Valley, the local name for the next valley downriver from Old Town, “it has seldom, if ever before; been my curiosity to meddle with the remains of the dead; but in passing a place on Harpeth river, some six or seven miles below the town of Franklin and belonging to Mr. Thomas Brown Esq; called Old-town — my attention was attracted; by the singular structure of quite a number of graves which were cut through by the road…” Click here to read a transcript of the full letter.

Josiah W. Nance and his sister Elizabeth Morton Nance (The Nance Memorial by George W. Nance, 1904, J.H. Burke & Co., Bloomington).

Now protected from disturbance by state law, under which it is a felony to dig up ancient human burials without a court order, the mounds and stone-box graves of Old Town would continue to draw curiosity seekers for over a century — often in concert with disturbance by improvements to Old Natchez Trace Road.

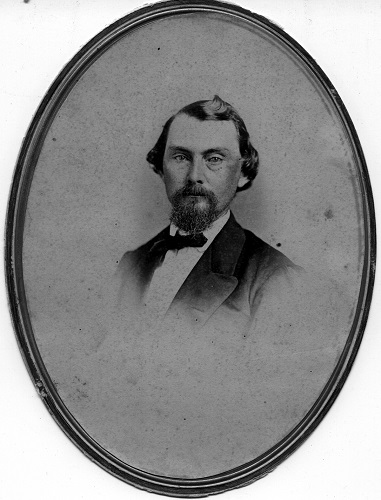

Old Town would also draw the attention of Dr. Joseph Jones (1833-1896), a former Confederate surgeon who served as Nashville’s first City Health Officer in 1867 and 1868. One of his side interests was ancient history and he is widely acknowledged as the first systematic investigator of the ancient mounds and graves of Middle Tennessee. Although only in Tennessee for two years, he explored numerous Mississippian mound sites, including Old Town which he noted in his first publication on his explorations, “one of the most remarkable stone-grave burying grounds is found on the west fork of Big Harpeth, six and a half miles from Franklin, at a place called Old Town, the property of Mr. Thomas Brown” (Jones 1869:58).

Jones would later (1876) publish a more extensive monograph on his Explorations of the Aboriginal Remains of Tennessee as No. 259 in the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge series. Recognized as one of the pioneer scientists of the New South, Jones was interested in graves not only for their artifactual “treasures,” but also as a medical doctor intrigued by the history of disease and health in ancient human populations. His Tennessee investigations were selected for publication by the Smithsonian in 1876 because they presented some of the best scientific evidence to dispel an embarrassing myth about a race of ancient Tennessee pygmies that was circulating internationally during the nation’s centennial celebration (Smith 2013).

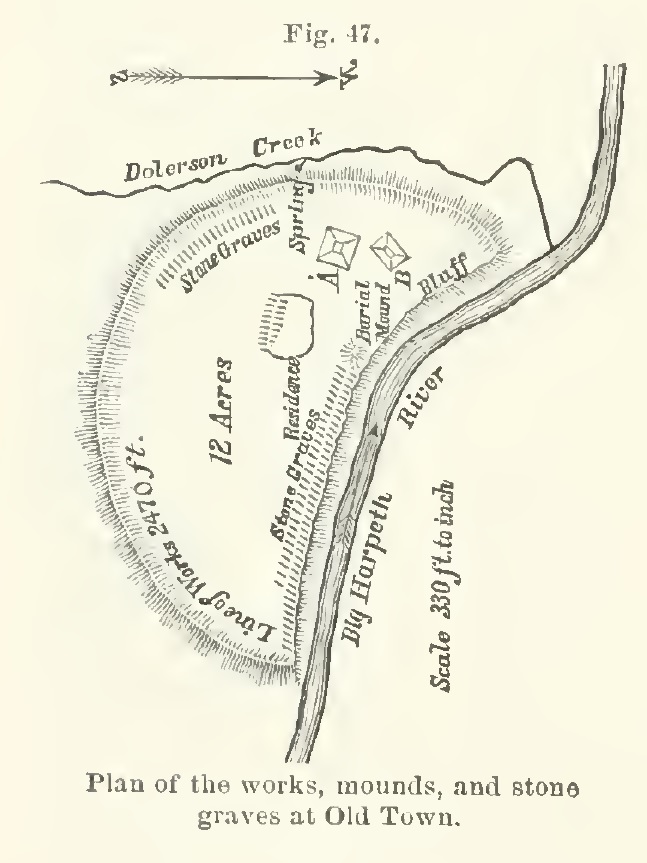

For our purposes here, the most important contributions of Jones are his descriptions of the visible features of Old Town in the 1860s — including production of the earliest known map.

At Old Town, on the land owned at present by Mr. Thomas Brown, the works extend in a crescent form from the steep bluffs on big Harpeth, 2470 feet in length, and inclose twelve acres. They contain two pyramidal sacrificial mounds, a small circular burial mound, a large burial mound now occupied by the family mansion, and numerous stone graves, ranging principally along the banks of the river.

The stone graves are numerous not only within the line of works, but also on the slopes of the hills and in the low-lands for two miles around, and the general appearance of the surrounding lands gives evidence of the existence in former times of a large aboriginal population.

At the present time the height of the inclosing earthworks varies from two to six feet; they have been much worn down by the ploughshare, however, and they are said to have been so steep and high thirty years ago that it was impossible to ride a horse over them.

The bluff on the river is abrupt… and a fine spring of water called the Bluff Spring issues from the banks within the portion included the line of works.

Two pyramidal mounds and a small burial mound are situated in the southwestern corner of the earthworks, near a fine spring, and within thirty feet of each other; the largest (A) is 112 feet in the long diameter, 65 feet in the short diameter, and 11 feet high; the next in size (B) is 70 by 60 feet at the base, and 9 feet high; and the small burial mound is 30 by 20 feet in diameter, and 2.5 feet in height. The house of Mr. Brown, located near these mounds and within the line of works, appears to have been built on a burial mound, for in excavating the foundation a number of interesting relics were found, and among them a vase the neck of which terminated in two human heads.

Joseph Jones, MD from his book, “Explorations of the Aboriginal Remains of Tennessee”

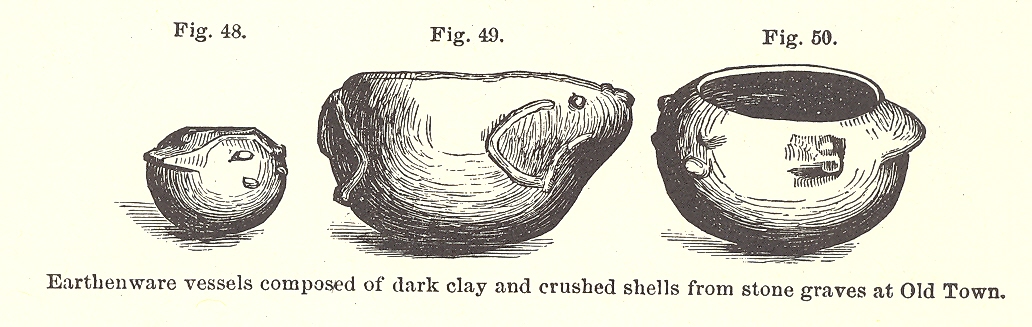

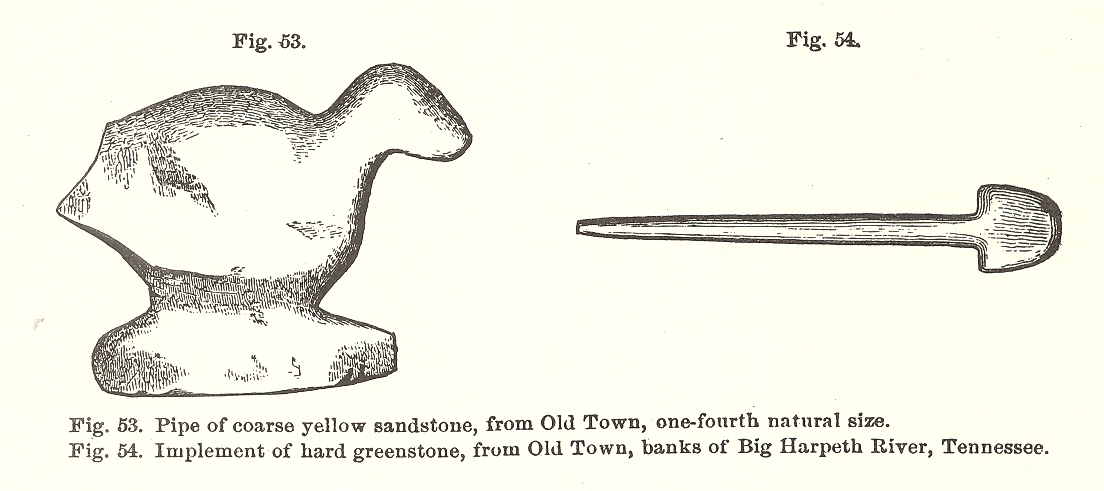

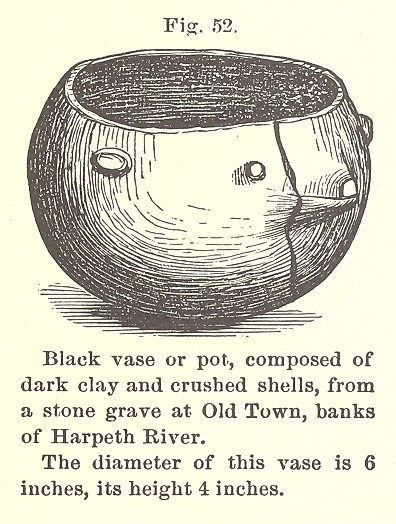

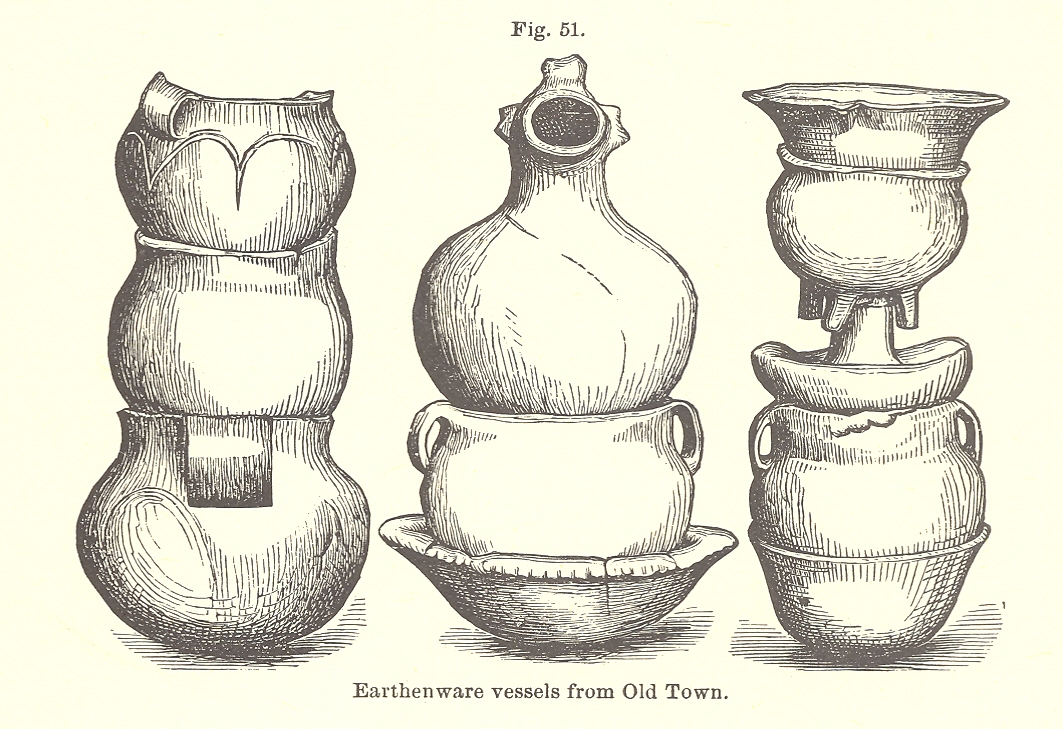

Jones goes on at greater length to describe his investigations and discoveries, and includes illustrations of several of the objects discovered at the time.

Illustrations of pottery and stone artifacts from Old Town (Jones 1876).

Jones’ publication of his discoveries in the nationally distributed Smithsonian series would ensure that the name Old Town became synonymous with the ancient peoples of Middle Tennessee. Jones’ private artifact collection was sold after his death to the Heye Museum of the American Indian in New York City, where it resided until those collections were transferred to create the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (Senator Frist is a member of the NMAI board). Read more about Dr. Joseph Jones’ life and work here.

Others who worked with Joseph Jones also left brief mentions of the Old Town, including Randal M. Ewing of Franklin (Republican Banner, 27 Oct 1868): “When I was a half-grown boy, in my hunting excursions I used to pass through an old Indian burying ground in our county a few miles west of Franklin, called Old Town. At that time it was a common sight to see numbers of skulls lying on top of the ground, where they had become exposed by the washing of rains…”

Dr. William Martin Clark (1829-1895) was another Franklin explorer who was paid by the Smithsonian Institution in 1875 to help gather evidence to dispel the myth of the “Tennessee pygmies” and to gather collections for the United States Centennial celebration, which was held in concert with the first major world fair and exposition held in the United States. Among the sites selected by Clark for examination was Old Town, where he also focused largely on graves and their “treasures.” He wrote in 1875:

“The most celebrated cemetery, and the one most frequently resorted to by relic-hunters is at “Old Town,” seven miles northwest of Franklin, on the farm of Mrs. Brown. Formerly, like other encampments, it had a wall and ditch surrounding it, but they are gone. There were many graves and mounds scattered over the inclosure. Most of these graves have long since been emptied of their contents, and the mounds, for the most part, have been dug into. However, I obtained some very interesting relics here, among them two beautiful pieces of ivory carved with a precision seldom seen among the Indians. They are made from a tusk, probably, of the mastodon.

The larger one must have come from the tusk of a monster, for to furnish materials for such a gorget it must have been 12 inches in diameter. These gorgets have two holes in the edge, near each other, and they were most probably worn suspended on the breast, and may have been emblems of authority. One of them was in the grave of a giant, for a large man could pass the lower jaw-bone around his face; and the thigh-bone was four inches longer than that of a man six feet two inches high. A piece was fractured off one edge by accident after taking it up. Another string of beads was procured here. They are made of bone, are quite small, and were lying in the grave of an infant. The dead in this cemetery were all buried with their heads toward the east, and some graves contained the bones of three or four persons. It was quite common to find the bones of children and adults in one grave, though occasionally a grave was occupied by several children. The relics, when there were any, were always found by the side of the skull.

Where they procured the material to make the greenstone axes found among their grave relics I cannot say, as it is a volcanic or igenous rock, and none is found in this State. It is said that a bluff on the Missouri River furnished the neighboring Indians with the material for these any many other implements.

A jar holding about two quarts, and a small pot, were exhumed. In the latter was found a piece of oxide of iron, weighing about two ounces, which shows a worn spot, where it had been scraped by the owners to obtain paint for their bodies. It readily yields a dusky-red color on being moistened. In one of the graves were found five beautiful oblong beads of amber, two inches long, and in the center one-half inch in diameter. They were smoothly bored, and, though showing some cracks were still entire. Unfortunately, they were stolen. They showed a fine polish, and would have been prized by our ladies very highly.“

Clark sent numerous specimens to the Smithsonian, which we presume were displayed in the “Stone Age” exhibit at the United States Centennial Celebration — including some from Old Town. Two that can be confidently identified are the two gorgets — made from the wall of a marine conch rather than mastodon tusk.

Unfortunately, like so many of his contemporaries, Dr. Clark left few other details of his observations and explorations.

Edwin Curtiss conducted a very brief exploration at Old Town in early to mid-October of 1878. He dug six stone-box graves along the side of a public road, but stopped after just one day of work. Curtiss noted these graves contained severely fragmented skeletal remains likely damaged by wagon traffic. A ceramic earspool comprised the only artifact recovered during this investigation (Archaeological Expeditions of the Peabody Museum in Middle Tennessee, 1877-1884).

Old Town on Harpeth River. 1 grave 6 ft 5 in long 22 in wide 14 in deep crania broken bones gone to dust head south east nothing but one ring of pottery in the grave and that broken pieces saved. I opened five others and found nothing but graves that had bin disturbed by wagons and stock as they were by the side of the public road. (October/November 1878; Link Farm, Old, and Gray’s Farm Notes, PMAE Accession Number 78-6).

In 1885 John B. McEwen (mayor of Franklin, lawyer, and farmer) wrote of “Fishing on the Harpeths in Early Days” (Spirit of the Farm, 6 May 1885): “The Harpeths in early days were famous fishing stream, and produced a great abundance of the finest fish… Traces of the Indians can be easily found along the banks of all these streams…. At a famous trouting point on Big Harpeth was an Indian town, known as Old Town, and hundreds of graves can be seen there all set around with stones placed edgewise. The location of this place, and the evidence of other camps along the different streams, all go to show that the Indian had an eye to business, and located at the best fishing and hunting grounds.” Click here for a 1903 biography.

In early 1920, Jesse Walter Fewkes, chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian, paid a visit to Old Town on his tour of local archaeological sites:

ETHNOLOGIST VISITS OLD INDIAN MOUNDS: Dr. Fewkes Accompanied on Franklin Tour by Mayor and Party. Special to the Tennessean. FRANKLIN, Tenn. May 5.– Dr. Jesse Walter Fewkes, chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology, accompanied by W.E. Meyer, spent several hours in the vicinity of Franklin yesterday, examining the Indian mounds and the remains of Indian fortifications.

At Franklin, the distinguished ethnologist and Mr. Meyer were joined by Mayor Park Marshall, who is deeply interested in ethnology and who conducted the party over the sites of the mounds.

Other points visited in Williamson County by the distinguished visitor and his party were the site known as Old Town, in the northwest section of the county, and Boiling Springs (Tennessean, 6 May 1920).

Franklin relic collector Luther McCall shared memories of a 1926 exploration of a cemetery at Old Town with Parmenio E. Cox:

Mr. McCall is variously distinguished as the owner of one of Franklin’s two collections of Indian relics, as a numismatist, a collector of fine antiques, and as a man who once quit his job to go fishing. Mr. McCall… told us that he had been interested in Indian artifacts since the age of 12, when an uncle visited his house with a particularly beautiful spearhead. This started him rambling over the fields, picking up flints and arrowheads. In 1926 McCall took a year’s leave of absence with pay from the Metropolitan Life Insurance company and, with the exception of Sundays, which he kept holy, spent just about the whole time with P.E. Cox, state archeologist, opening Indian graves and mounds. They opened 25 or 30 graves on the Harpeth river at a place called Old Town. They opened a burial mound with six small burials on the top, one of which yielded up a small bowl with the skeleton of an opossum in it. When they had dug through the first six layers they were still working in old dirt and decided to dig further. Four inches deeper they ran into seven skeletons — six women and a man who was over seven feet tall. ‘The jawbone covered my face like a mask,’ McCall told us. The giant warrior had evidently encountered a foe just a little bit bigger than he was, and his six wives were buried with him, as was the custom in those days. The skeleton of a medicine man yielded 960 beads, arranged in bands about his ankles, knees, wrists, and chest, and a mussel shell full of red ochre still in a usable condition… In April 1885, the river got up at Franklin, and Mr. McCall and a playmate Harry Williams, played hooky from school one afternoon to go fishing in the backwater’s of Brown’s creek. They found a long-necked beer bottle and decided to write a note, insert it, and set the bottle adrift. This they did. Mr. McCall wrote “if you find this bottle please open it and send me this note.” Twenty years later, Henry Pointer, who was at that time connected with the Williamson County bank, was visiting in Arkansas, about 40 miles from the Mississippi river, when he was approached by a man who asked if he knew L.A. McCall in Franklin. Well, the Arkansas man had the note, and Pointer returned it to McCall (Variously Distinguished, Nashville Tennessean Magazine, 8 Aug 1948).

During the summer of 1928, William Glass Polk examined about 80 graves from a cemetery located near the junction of the Harpeth River and Dolerson Creek (Polk 1948). This work was performed prior to their destruction by heavy machinery. One artifact of interest recovered from this work was a human head effigy pendant made from sandstone. Other specimens from the site included five marine shell “vessels” and an owl effigy hooded bottle.

Polk, a Franklin resident, amassed a collection of over 30,000 artifacts in the 1920s and 1930s. Although his collection was donated in 1981 to the Tennessee State Museum by his widow Mary, no inventory indicating where the objects were recovered was available at that time. Hence, while many or all of the objects from Old Town are probably present in the museum collections, only one can be confidently identified at this point — “another interesting relic is a sandstone image which resembles and Egyptian. This piece was found while constructing a bridge over Donelson Creek, which has proven to be a large burial ground. Mr. Polk began his study of archaeology about eight years ago. He has continued to add to his collection during that time and his work has attracted much interest among other workers in the field, who have found the young man’s collection to be one of the finest in the south.” (Franklin Review Appeal, 25 May 1933).

Unfortunately, despite the intense interest in the Ancient Old Town spanning a century, this era is characterized by what might best be described largely as a search for treasures amidst the graves of Old Town. Although the objects that survive from these explorations have a few things to tell us about the ancient inhabitants — the lack of details and context render them more specimens of art than of archaeology.

As stewards of Old Town, we started the Old Town Heritage Project with Middle Tennessee State University to synthesize for the first time all of the tidbits of information about this ancient town that are preserved in publications, notes, and museum collections across the breadth and width of the eastern United States. Many important questions remain unanswered — and our project is moving forward primarily with non-destructive geophysical investigations but also with some very small-scale and targeted archaeology to answer some of those questions without further significant disturbance. Read more at the Old Town Heritage page. Our purpose is to pursue and share broadly knowledge about our collective past to more fully understand who we are as a people today.

Although the story of the “Old Town” starts long before “history,” it is an important part of the living heritage not only of modern Native Americans, but also of us all.