Following a series of megadroughts that drove the native peoples from the Middle Tennessee region in the 1300s and 1400s, the area was largely uninhabited until the earliest explorers came nearly three centuries later. These explorers recognized it had been a heavily occupied place long before. A mystery to them, they immediately referred to it as “the Old Town” — a name that persisted and later also became attached to the Thomas Brown House and the land surrounding.

The following is an excerpt from Albert Ganier’s “The Saga of Nicholas Perkins,” written in 1964.

“Major Nicholas Perkins, by 1815, had come to the conclusion that he would give up the practice of law in [Franklin] and that he would lead the life of a country gentleman, there being by now plenty of land in the family. On October 29, 1816, he sold the 47-acre tract on which he lived, for $6,000, to John Price and Turner Saunders. The purchasers immediately divided it into lots and streets, thus forming Franklin’s first subdivision. Nicholas quite likely leased his former house and continued to live in it a few years more. He is not shown on the tax books as owning a city lot so presumably he gradually divested himself of his law practice and proceeded to devote his time to his and his father-in-law’s plantations. Thomas Harden Perkins was now (in 1815) fifty-eight years of age and was paying taxes on 3,000 acres of land and 42 slaves.

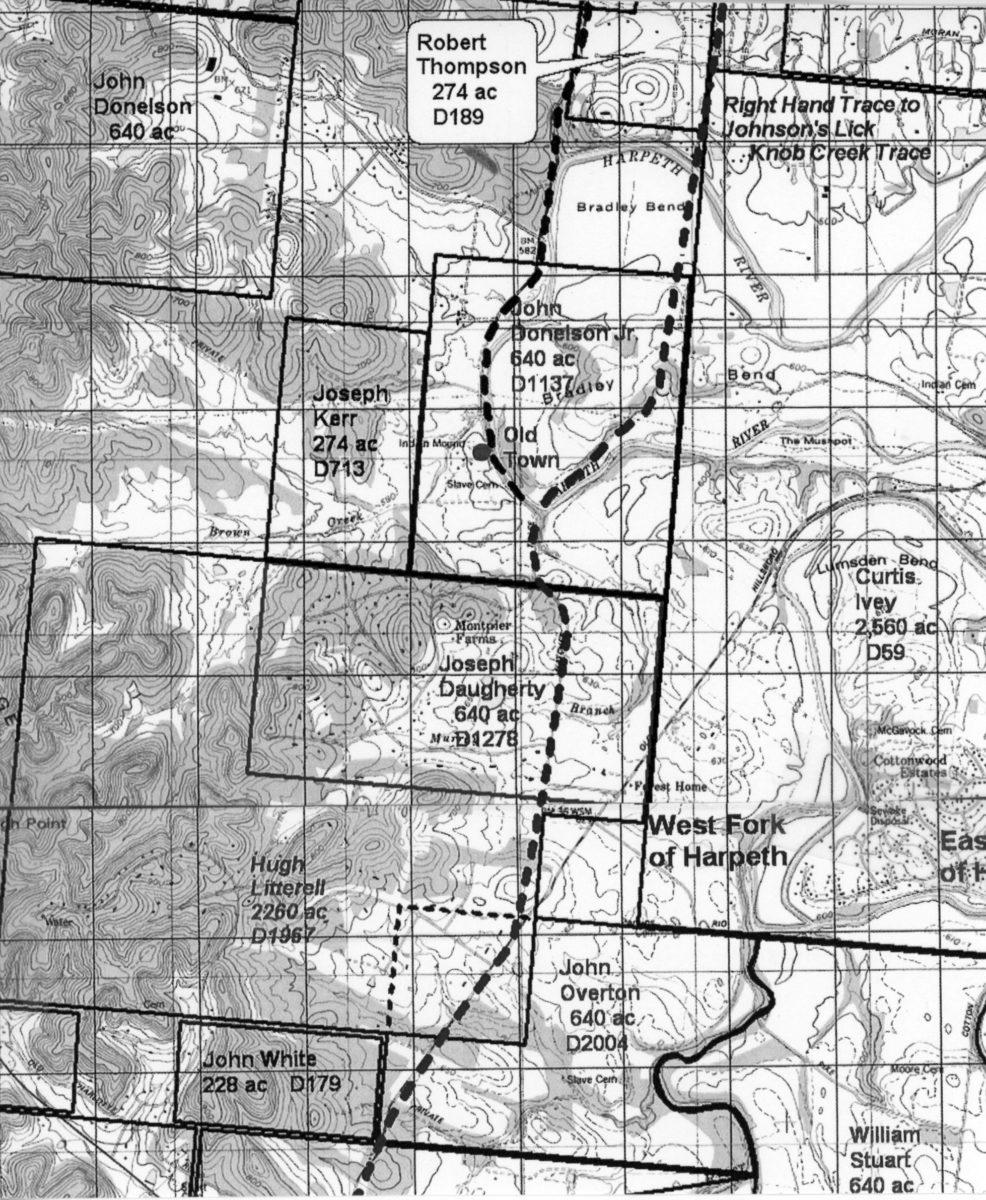

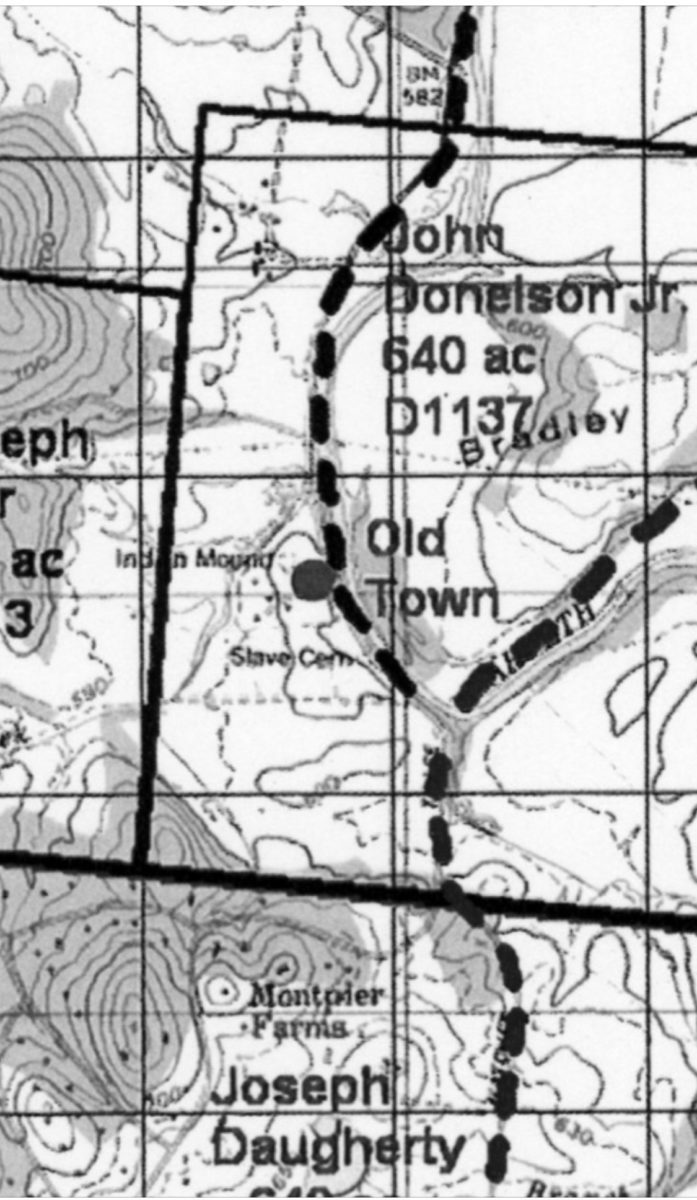

Major Perkins’ choice for a new home was the Old Town Plantation, there being some excellent log dwellings on it at that time. It was on the old Natchez Road and this road divided the front lawn from the bank of the Harpeth River. It was two miles northward from Harden’s home. The father-in-law was so pleased that Nicholas had decided to become a neighbor that he presented him with a very large tract of land, comprising 1,216 acres on the Harpeth River. He had purchased the tract from John Donelson Jr. In 1818, paying him $12,116 for it. On February 3, 1819 he deeded the land “…for and in consideration of the love and affection the said Thomas Harden Perkins has for his daughter, Polly Harden Perkins, the said Thomas Harden Perkins hath this day given, granted and conveyed unto the said Nicholas Perkins Jr., …”

The Old Town place had derived its name from the fact that it had, in prehistoric days, been the sight of an Indian town, as evidenced by several low mounds within a stones’ throw of the river and an extensive Indian graveyard. Excavations later made here, in 1868, by Dr. Joseph Jones of the Smithsonian Institution, produced a large number of fine artifacts such as clay vessels, images, flint implements, etc. taken from the stone-lined graves. The land was part of the grants that had been given to John Donelson Sr. the Nashville pioneer of 1780, and inherited from him by his son, John Donelson Jr. after the mysterious death of his father in 1789.

The tract of land was well watered by Donelson’s Creek, was nearly level, and included a river bottom across the Harpeth which could be reached by using a rock ford. Adjoining Old Town on the south was the extensive Littrell tract owned by his father-in-law, including the Montpier tract on which he was to later build a pretentious brick mansion for himself and his family. Old Town remained in the possession of Major Perkins until 1840 at which time he sold it to his brother-in-law, William O’Neal Perkins of Florence, Alabama. The latter at once sold the tract; the one-fourth part of it next to the river being conveyed to Thomas Brown who within a few years replaced the old log dwelling with the present auspicious home of timber construction.” [1]

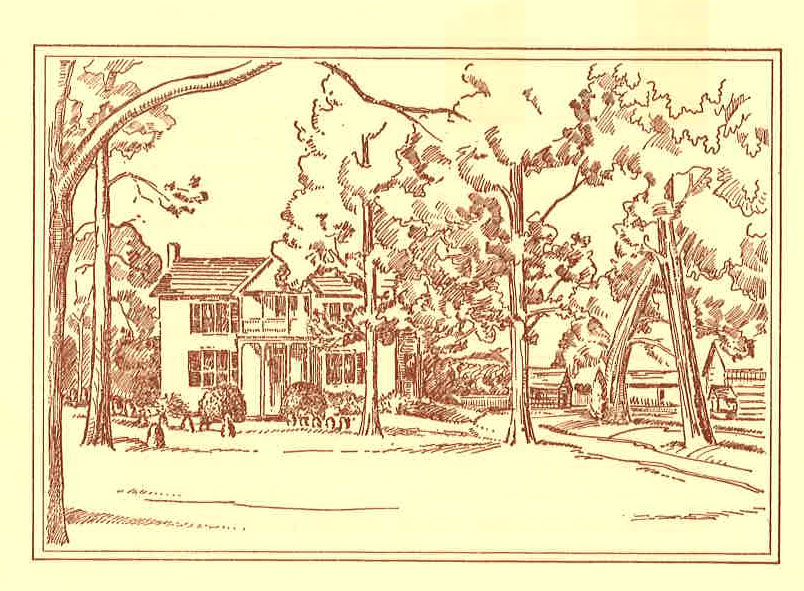

Constructed by Virginian Thomas Brown in 1846, the Greek Revival-styled home stands serenely at the juncture of the Big Harpeth River and Donelson’s Creek (now called Brown’s Creek) with the original, well-travelled Natchez Trace just east of the house. According to a short written history of the property, “All of the timber used in the house was cut on the farm. The bricks used in the chimney were burned on the place and remnants of the kiln are still visible.” [2]

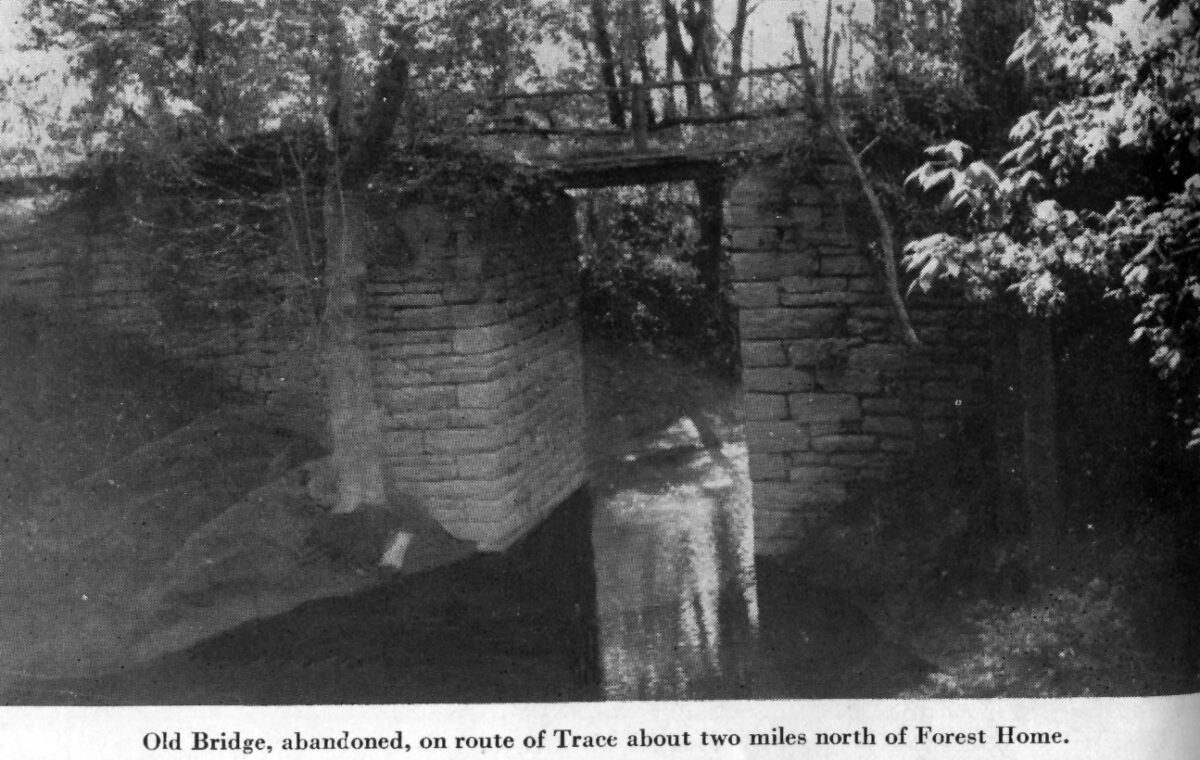

The Old Town Bridge, built by federal soldiers in 1801 for the passage of mail and troops, is one of the oldest surviving bridges in Tennessee. Its construction was ordered by the Secretary of the War, and “stands as a picturesque monument to the skill of early stone masons and as an excellent example of early American bridge construction.” [3] Andrew Jackson and his troops crossed the bridge on the way back from the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.

A huge pecan tree which once stood 80 to 100 feet tall on the south side of the house, is said to date back to the time of Andrew Jackson and lived well into the 20th century. According to one history of the property, an Old Town neighbor “whose ancestors fought with Andrew Jackson, and who on his ancestral estate had a similar tree which was recently destroyed by a windstorm, stated that his ancestor brought the pecans back when returning from the Battle of New Orleans and planted a few in the neighborhood of which the towering giant of Old Town is the only one remaining.” [4]

Excerpt from Virginia Bowman’s book Historic Williamson County: [5]

John Donelson, one of the founders of Nashville, owned the Old Town tract at one time proving that it was a well-known landmark from Tennessee’s earliest days. The property laid along an oft-traveled road since a section of the Natchez Trace ran between the present road and the Big Harpeth River which is in calling distance of the house.

Parts of the old Trace are still visible here following the west bank of the river before it angles off across country again. As an Indian trail even before the wheels of covered wagons cut the bed six feet deep, the Natchez Trace was one of the most historic roads in America. Its sinister, yet fascinating history, was so often splotched with the blood of its travelers the sight of a scarlet leaf on the overgrown path makes the modern day researcher hesitate – remembering. …

Thomas Brown (1800-1870), the son of Joseph and Catherine Browne, was born at Brentsville in Prince William County, Virginia, and moved to Williamson County with his younger brothers and sisters soon after his father’s death in 1822. He did not buy the Old Town tract from William O’Neal Perkins until 1840 and did not begin construction of the house until 1846. During the six intervening years, the Browns lived in a cabin on the place. Where they lived before moving to Old Town is not known, but they were thought to have lived close by.

In 1828 Thomas Brown married Nancy Allison (1810-1838), the daughter of Hugh and Lydia Allison of Linton. Nancy Brown died young leaving two small sons, Hugh and Joseph Allison. She was buried with her parents at South Harpeth. Three months later, in the same ruts made by the wagon carrying the first wife’s coffin to the cemetery, jounced the carriage bringing the new wife home. She was Margaret Smith Bennett Hunter (1807-1888), the daughter of George and Anna Dabney Bennett who had moved to the Hillsboro community from Chatham County, North Carolina, when she was just a child. She married James M. Hunter in 1823, but he was killed out west shortly afterward.

Society did not frown upon such marriages of convenience in the old days. Mrs. Hunter had been a close friend of the first Mrs. Brown; in fact, she had been asked to lay her out, a service performed by only the closest family or friends. Mr. Brown needed a mother for his little boys, the youngest of whom was very frail. Their ages were compatible, their social standing unimpeachable, their mutual interests many.

Since these weddings generally followed immediately upon some devastating loss, emotions were often still raw. Mrs. Brown told years later of waking those first few months to the disconcerting sounds of her husband weeping for his first wife. He would smother his sobs with a pillow and, lying silently in the dark, she would feel tears of grief for her first husband sliding into her hair. It is a mark of the mental and emotional stability of earlier generations that such couples adapted to change and lived happy, well-adjusted lives.

For the building of the residence at Old Town, Pryor Lillie, the contractor, used [enslaved people] and materials from the site. All yellow poplar and longleaf pine timbers were hand sawn and joined with pegs and square headed nails. When completed, it was a sturdy two-story frame dwelling with a small two-story porch and was located some eight miles northwest of town.

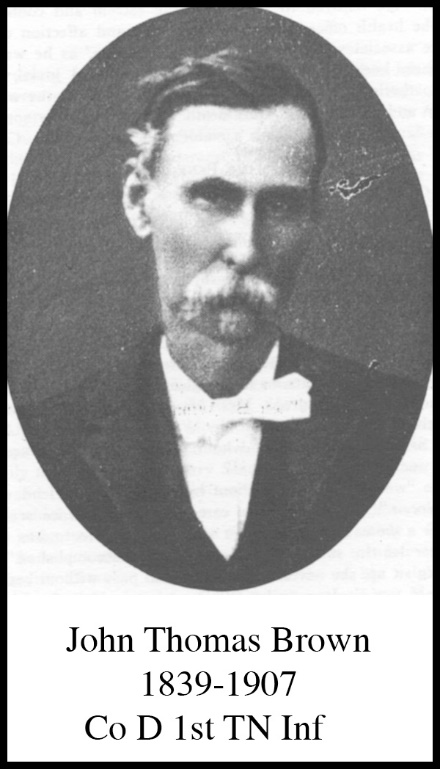

Thomas and Margaret Brown had four children – John Thomas, Bethenia, Jane, and Margaret, who married into the French, Miller, Bowman, and Kirkland families. Little Hugh died as a child and Joseph Allison died a young man in 1857. Called Devil Joe because of his wild ways, he had been put against his stepmother by the servants when he was a child, and upon her arrival he met her with a scowl and said, “You’re ugly.” So kind was she to him over the years when he lay dying, with his fox hounds howling mournfully under his window, he turned to her and whispered with his last breath, “Mother.”

Cultural Context of Pre-Civil War Historical Periods [6]

Exploration (1770–1795)

European hunters began exploring this area in the 1700s. In 1775, speculators illegally purchased land, including the Old Town area, from the Cherokee Indians in the Transylvania Purchase. In 1775/1776, all of present-day Tennessee became the Washington District of North Carolina. Washington County, also named after General George Washington, was created in 1777.

North Carolina established Tennessee County in 1788, which encompassed the study area. Two years later, North Carolina ceded rights to all its lands west of the Great Smoky Mountains, including Tennessee County, to the federal government as the Southwest Territory, which would become the State of Tennessee.

In 1790, North Carolina established the North Carolina Military Reservation along the Cumberland River Valley. Scores of Revolutionary War veterans soon arrived from North Carolina to claim land grants in the reservation as payment for their military services. Settlers also migrated from other states, primarily Virginia. This area, which became known as the Cumberland Settlements, centered on river towns such as Nashville and Clarksville. In 1790, the population of the Cumberland Settlements, including Davidson (1783), Sumner (1786), and Tennessee (1788) counties, was estimated around 7,000 (Corlew 1990:100).

Early Settlement and Development (1795–1830)

In 1796, the Southwest Territory was admitted into the Union as the State of Tennessee. White settlers began trickling into the study region by the late 1790s, initially settling the fertile bottomland along rivers and creeks, where they established farms operated by enslaved African Americans. Williamson County, the seventeenth formed in the state, was carved from Davidson County in 1799, and the county seat of Franklin, named after Benjamin Franklin, was laid out near the Harpeth River. The county itself was named for Dr. Hugh Williamson, a Revolutionary War patriot and distinguished statesman from North Carolina. Ewen Cameron built the first house in Franklin, and subsequently other families from Fort Nashborough, which became Nashville, moved south to the area. Many of Franklin’s early settlers came to assume land grants awarded for their Revolutionary War service. Private schools flourished in the area, drawing additional settlers. The county’s population grew from 2,868 in 1800 to 20,640 in 1820 (Acuff 2010).

Antebellum (1830–1860)

Prior to the Civil War, Williamson County had become the third wealthiest county in Tennessee, due to its agricultural industry. Hundreds of farms, small and large, occupied the county, with the majority of commercial and social activity centered on Franklin. Communities arose in Nolensville, College Grove, Triune, and Leiper’s Fork as centers for area farmers. Several public and private roads serviced the county, including the Wilson Turnpike, Nolensville Pike, Lewisburg Pike, and Carter’s Creek Pike. By 1860, the Tennessee and Alabama Railroad was completed, effectively causing the growth of railroad communities such as Thompson’s Station and Brentwood. The population of the county remained stable at around 27,000 throughout this period, with Franklin counting around 900 people in 1860 (Thomason and Matter 1987).

Thomas Brown moved to Williamson County in 1822 and, in 1840, purchased from William O’Neal Perkins the land where the study area is located (National Register Keeper 1988a). Brown began construction of the two-story mansion around 1846 using builder Pryor Lilly as the contractor. In 1860, Brown was listed as having real estate valued at $25,000 and personal property valued at $34,500. By the time of his death in 1870, he owned 546 acres of land along the Harpeth River.

Sources:

- Ganier, Albert F., “Nicholas begins life anew in Tennessee,” The Saga of Nicholas Perkins, 1964, ch. 9.

- Goodpasture, Henry and Virginia, Old Town, 1950, p. 9.

- Bowman, Virginia McDaniel. “Old Town.” Historic Williamson County, Blue & Gray Press, Nashville, 1971, pp. 91-93.

- Goodpasture, Henry and Virginia, Old Town, 1950, pp. 10 – 11.

- Bowman, Virginia McDaniel. “Old Town.” Historic Williamson County, Blue & Gray Press, Nashville, 1971, pp. 91-93.

- Geophysical Survey of Old Town Archaeological Site (40WM2) Williamson County, Tennessee by New South Associates, Inc., Sarah Lowry (Principal Investigator), September 20, 2019.