A thousand years ago Native People chose a special place to settle. Old Town was the perfect spot. They chose fertile fields, access to natural springs and navigable waterways, and abundant opportunities to fish. They chose a high ground, to protect them from floods and warring aggressors, at the juncture of a meandering, spring-fed creek and a much more commanding, steeply banked river that connected them to hundreds of miles of waterways for transportation and commerce. That creek is present day Brown’s (formerly Dollison) Creek and the river, the Great Harpeth.

Both the creek and the river exist today much as they did in ancient times. The Harpeth River over the centuries has been allowed to flow freely unencumbered by dams and controlled flow that govern most every other river in Tennessee. Today the Harpeth rises and falls as much as 20 feet, usually over a period of hours or days, several times a year, topping the steep banks and closing all road access to Old Town from the North and the East.

Brown’s Creek, at rest tightly serpentine in course for the two hundred yards closest to the Harpeth, will correspondingly rise, dramatically becoming a transient (three days at most) lake 50 yards across as the Harpeth crests. These dramatic fluctuations of nature, so magnificent and visual, are a recurring, humble reminder of the majesty of the world around us.

Brown’s Creek

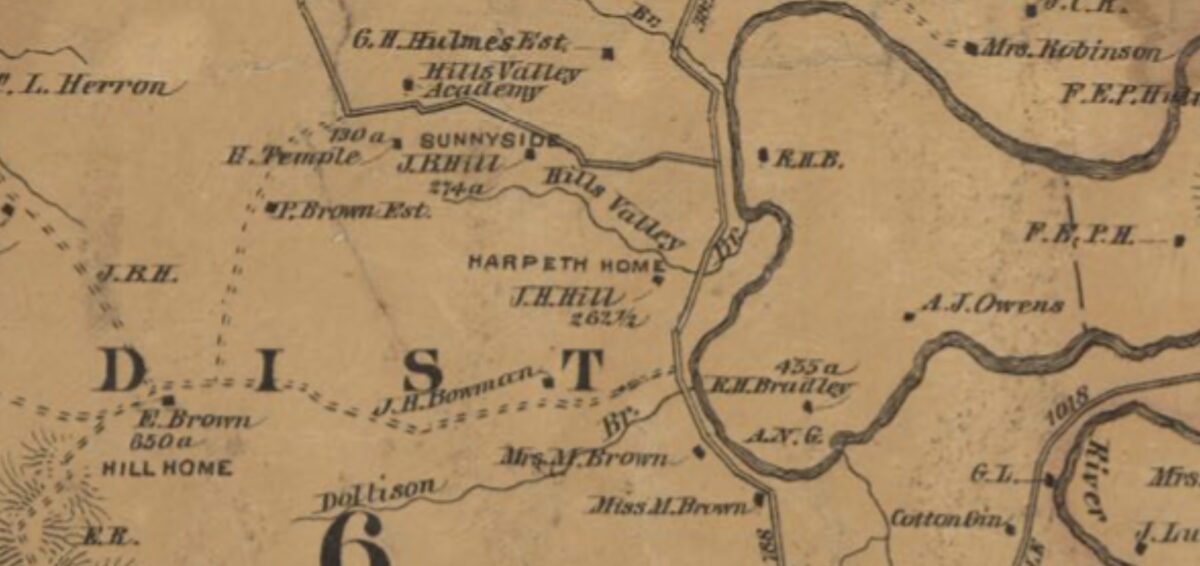

Brown’s (formerly Dollison) Creek has little provenance from historical writings, but what we can reasonably assume is that it played an important role in the everyday lives of those original hundreds of families who lived at Old Town around the time of 1050 to 1300 AD. The earliest hand drawn maps of Old Town depict the creek (labeled “Dolerson Creek” by James Jones in his 1876 treatise and Dollison Creek on a map XXXX from 1878) prominently, with specific notation of a “spring” conveniently adjacent the large, palisaded wall that surrounded the 12-acre town center. That protected and nearby source would have been especially significant in times of war or threat by outside invaders.

We don’t know the original name of Brown’s Creek. Could it have been Donelson’s Creek, after John Donelson to whom this land was originally granted by the state of North Carolina? Donelson left the property to his son John Donelson, who later sold it to William O’Neill Perkins. As noted, the 1876 publication by James Jones referred to the creek as “Dolerson Creek.” Whether this was a mistaken play on Donelson Creek or referred to an actual Dolerson person or family is unknown.

Our family spends much of our time in nature on the banks of this creek. Shallow enough to traverse in water boots on most days, we cross it regularly to access the meadows and woods which comprise the western half of Old Town today. Our four Australian shepherds gravitate after their daily run to the woods and fields to the very same spring site that Native Peoples relied on in prehistoric times. The banks of the creek host our annual Father’s Day picnic with grandchildren exploring the creek looking for relics, skipping rocks, respectfully chasing the tadpoles, and hiding beneath (yes, beneath) the exposed massive eight-foot deep tree root systems that have been sculpted by those-every-few-month times that the creek reaches raging levels with heavy rains and the fluctuating Harpeth. Around the last bend of the creek trek toward the Harpeth, one discovers the towering, magnificently crafted, dry stacked stone bulwark of the 1801 Old Town Bridge (see 1801 Bridge).

The Great Harpeth River

The Great Harpeth has a biography. The river flows to the Cumberland River for 117 miles, westward from present day Rutherford County (the geographic center of Tennessee) to just below Ashland city, northwest of Nashville. It runs in and out of five Middle Tennessee counties. The Harpeth attracted many thousands of prehistoric Native Peoples in villages scattered along its winding course.

The Harpeth flows along the eastern border of Old Town, the Old Town property uniquely deeded to include half of the river itself. These steep banks, enjoyed today by family fishing and canoeing, are the eternal resting site of many hundreds if not thousands of Native Peoples buried in stone box graves in ancient times.